Let’s say you decided to start a new project, one that requires significant investment of effort on your part and has an element of uncertainty. This can be an academic project, a new start-up, or maybe you’ve decided to start a new year resolution.

A fair assumption may be that we wish to succeed in that project we’ve started.

If this project happens to be related to scientific research or entrepreneurship, then odds are not to our favor. I’ve been told on several occasions that the failure rate of projects in either category is more than 90%. This statistics forms the pillar of several success-related famous quotes, my personal favorite being one from Warren Buffett:

The difference between successful people and really successful people is that really successful people say no to almost everything.

What Mr. Buffett neglected to advise is how to pick out what is part of almost everything and what would be the occasional something where ‘yes’ is the right answer.

So sometimes, we end up committing to projects before we have enough information (or the guts to overcome the academic fear of missing out) to say ‘no.’ When I first began training, one of the most salient advice was that a trainee should “stick with your project and see it through.” The most helpful mentors sometimes nudge their trainees along the path by asking “what’s the best next step?”

But what if the “best next step” is to stop “seeing it through?”

If starting a new research project is like driving down a long road with many forks but only one correct path, then the endpoint may be like getting to White Castle at the end of that road trip. And that each of the forks leads to a cliff.

The problem is: when you’re at a fork in the road, all you see is the fork. You don’t see White Castle, and you certainly don’t see the cliff.

While everyone wants to find a White Castle at the end of their sober, not otherwise herbaceously enhanced academic road trip, knowing the statistics that 9 out of 10 roads lead to a cliff naturally leads to a different approach:

If the best thing that can happen to a project is to succeed, then the second best thing that can happen is to know exactly when it was going nowhere. Unfortunately, sometimes you just keep driving after making a turn, not knowing where the end of this fork leads.

The worst part is that the more you drive along a forked branch, the more committed you become to it, and the harder it is to stop and turn around.

I have been advised numerous times to define endpoints, visualize the White Castle at the end of the trip, smell its hamburgers, and at every step find the next best action to get there. Although sound, maybe it is an incomplete advice. What if the best thing to do is to turn around and start over? How will I know when it’s time to move forward and when to stop?

Harvard Business School gives this approach a fancy name called Discover-Based Planning, one element of which involves an inverted income statement where entrepreneurs are encouraged to start by writing down a Net Income forecast necessary for the nascent start-up to survive. Then, assumptions are added one by one – if these are the bottom lines, then when must the next rounds of funding happen? What must our operating profit be? How many widgets must we sell to achieve these numbers?

The first generation Amazon Kindle was designed with the instructions that the engineers can do whatever they want as long as the device has 3G connectivity, long battery life, easy to hold, and use ink-like screen, a stringent set of criteria set by the CEO Bezos as necessary for success, without which the project becomes no longer worth pursuing.

Mr. Buffett knows how to be very successful by saying no to almost everything. But for those of us who don’t have the same acumen, we may fare better by creating internal checklists and establishing hard-stops that makes the next “no” easier to say to our hardest customers – ourselves.

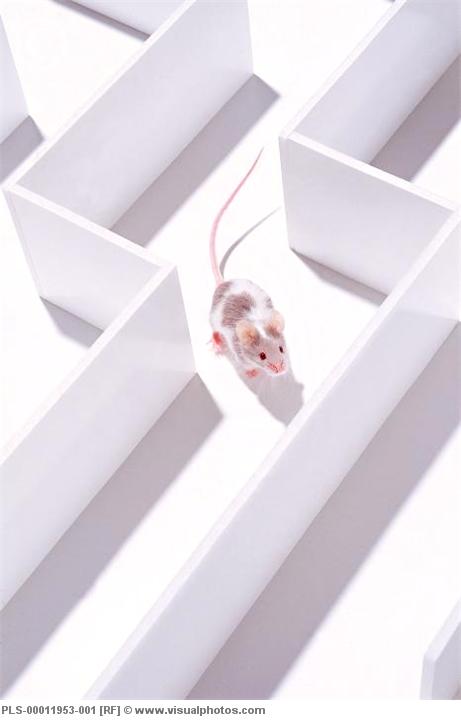

Envision a mouse trying to solve a maze for a piece of cheese, and he has to decide which way to turn at the first cross-section. He takes a look at the three possible routes, thinks for a bit, then turns a sharp left and ran. In a complex labyrinth, the mouse would most likely reach a dead-end by blind guessing.

Envision a mouse trying to solve a maze for a piece of cheese, and he has to decide which way to turn at the first cross-section. He takes a look at the three possible routes, thinks for a bit, then turns a sharp left and ran. In a complex labyrinth, the mouse would most likely reach a dead-end by blind guessing.